How the Case Study House Program Inspired a California Modernist Movement

75 years of influence.

-

CategoryArchitecture, Arts + Culture, Design, Homes + Spaces, Time Capsule, Vintage

-

Written byGail Phinney

-

Photographs courtesy ofThe Julius Shulman Collection at Getty

The story of the development of Los Angeles in the mid-20th century mirrors that of many postwar communities in America. A rising middle class sought suburban refuge and a leisure lifestyle. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, known as the G.I. Bill, provided a range of benefits for returning World War II veterans including low-cost mortgage loans.

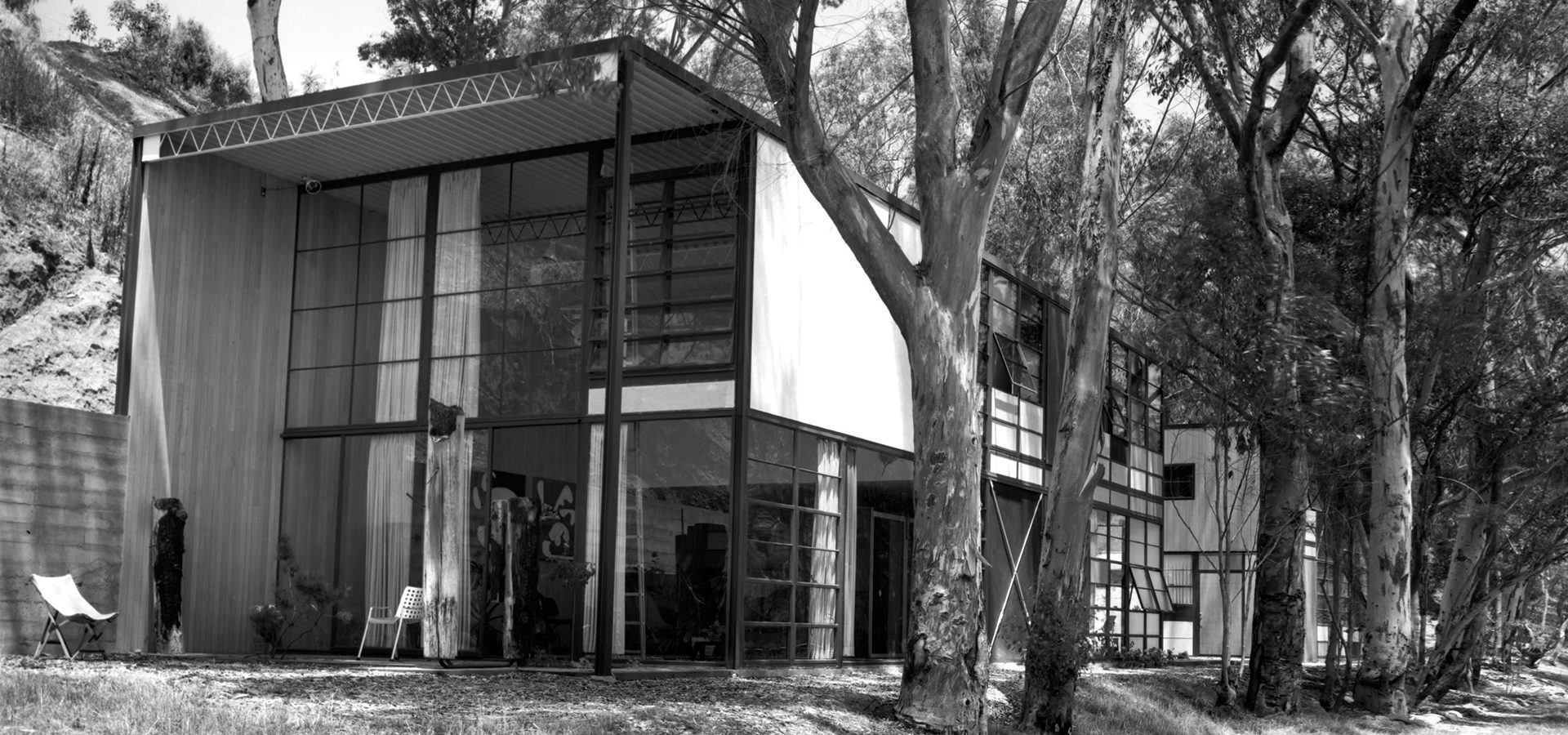

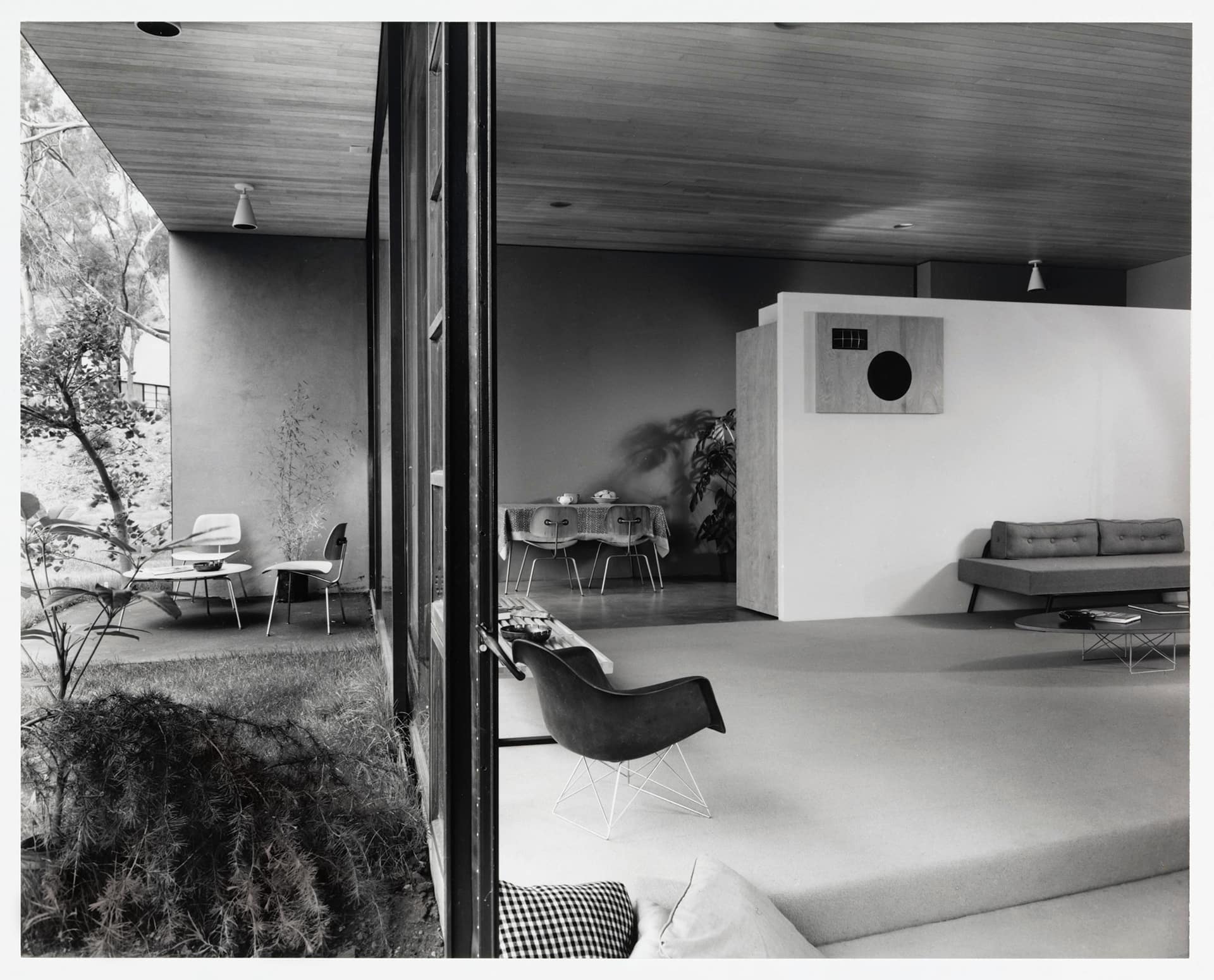

Ray and Charles Eames at home

What made Los Angeles unique was the wartime growth of the aerospace industry that brought an influx of workers from across the country attracted by the scenic landscape and proximity to Hughes Aircraft Company, Douglas Aircraft, Northrop Corporation and Lockheed Industries. As a result, Los Angeles County became the fastest growing metropolitan area in the United States.

And with this rapidly growing population came a need for relatively affordable, replicable houses for post-World War II family living. All this set the stage for the Case Study House Program.

The brainchild of publisher and editor John Entenza, the Case Study House Program was announced in the January 1945 issue of Arts & Architecture—a magazine dedicated to showcasing the best art and design of the period. The idea was simple: focus on using modern means to solve the postwar housing crisis in Los Angeles by expanding the definition of the word “house.”

While Entenza was not an architect, he was a visionary champion of modernism as an architectural style. More importantly, he was passionate about supporting and promoting innovative design that would result in good housing and living in a modern way.

Charles Eames in Case Study House #8

To that end, Entenza personally invited architects to design eight houses, and the magazine would feature one each month. The initial architects included J. R. Davidson, Sumner Spaulding, Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen, William Wurster, Charles Eames, John Rex, Ralph Rapson, Whitney Smith and Thornton Abell.

It was his charge that “the house … will be conceived within the spirit of our time … best suited to the expression of man’s life in the modern world.” In fact, the program continued on and off until 1966, outlasting Entenza’s tenure with the magazine.

Esther McCoy, who chronicled the program and later wrote the book Case Study Houses 1945–1962, said, “No one single event raised the level of taste in Los Angeles as did Arts & Architecture; certainly nothing could have put the city on the international scene as quickly.”

ABOVE: Case Study House #8

All in all, Arts & Architecture commissioned 36 houses and apartment buildings. Although many of the early designs were not built, the Case Study House Program succeeded in producing some of the period’s most important works of residential architecture in a style that continues to fascinate and evoke the ideals of Southern California living.

If you are not familiar with the magazine, its editor-publisher or some of the Case Study House architects, you are not alone. Even in its heyday, Arts & Architecture was a professional magazine not well-known by the general public. What brought the Case Study Houses into the public consciousness were the winning combination of Entenza’s singular dedication to modernism and his mastery of public relations.

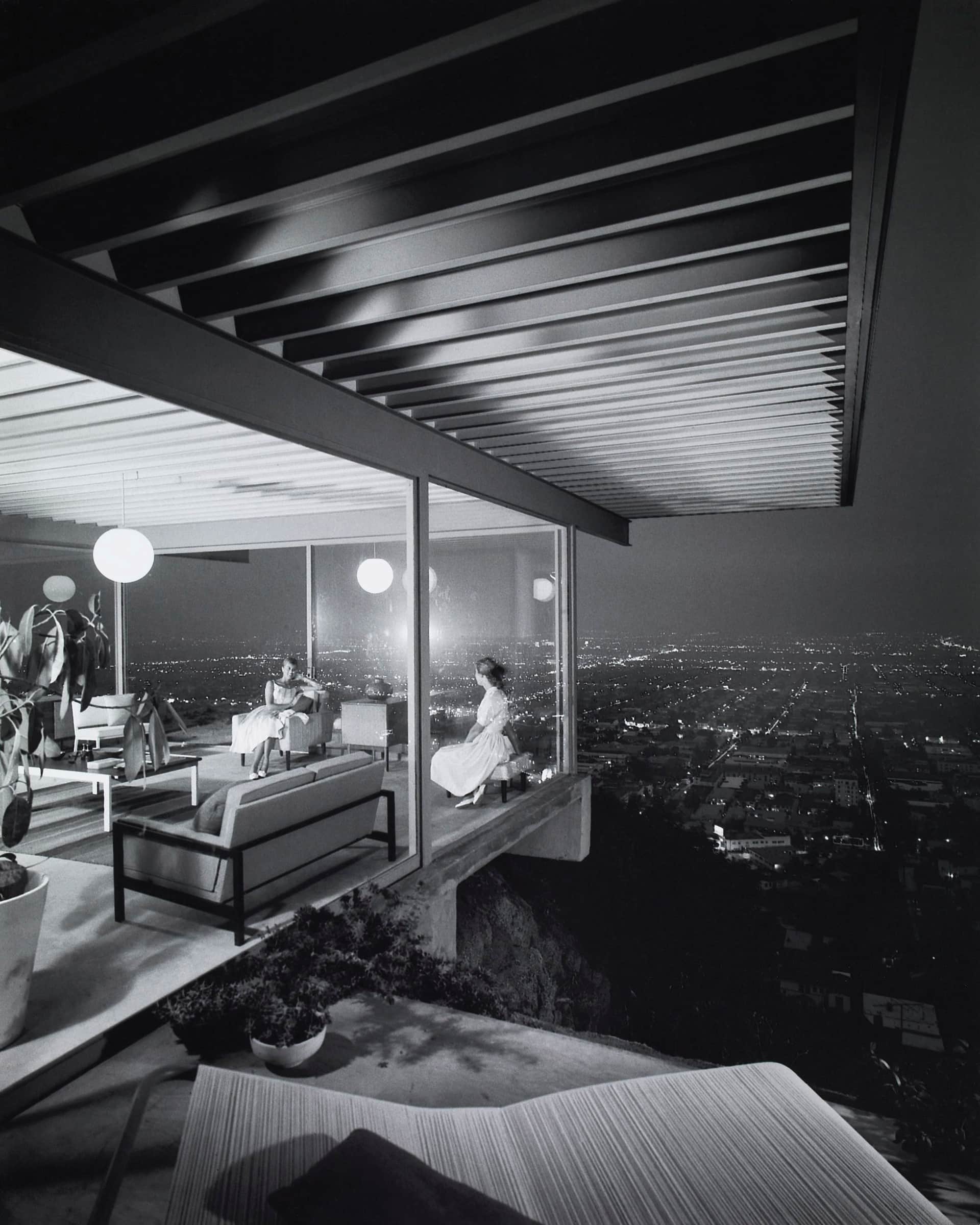

Case Study House #22

The Case Study House Program was imagined as a design-publish-build project. When completed, the houses would be open to the public for a period of six to eight weeks. This was not only a practical means to measure the success of the design; it was a way for the architects to receive donated building materials and product placement from high-end furniture manufacturers such as Herman Miller Company in exchange for the publicity generated by McCoy’s column promoting the program in the Los Angeles Times.

Prior to the Case Study House Program, modernism was already flourishing in Los Angeles. Frank Lloyd Wright brought his brand of modernism to L.A. with his 1919 textile block Hollyhock House. With him came Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler, both steeped in the Bauhaus tradition. Schindler’s 1922 multifamily Kings Road House is revered for its indoor/outdoor open floor plan, sliding glass panels and unique use of industrial materials—so innovative and influential for its time.

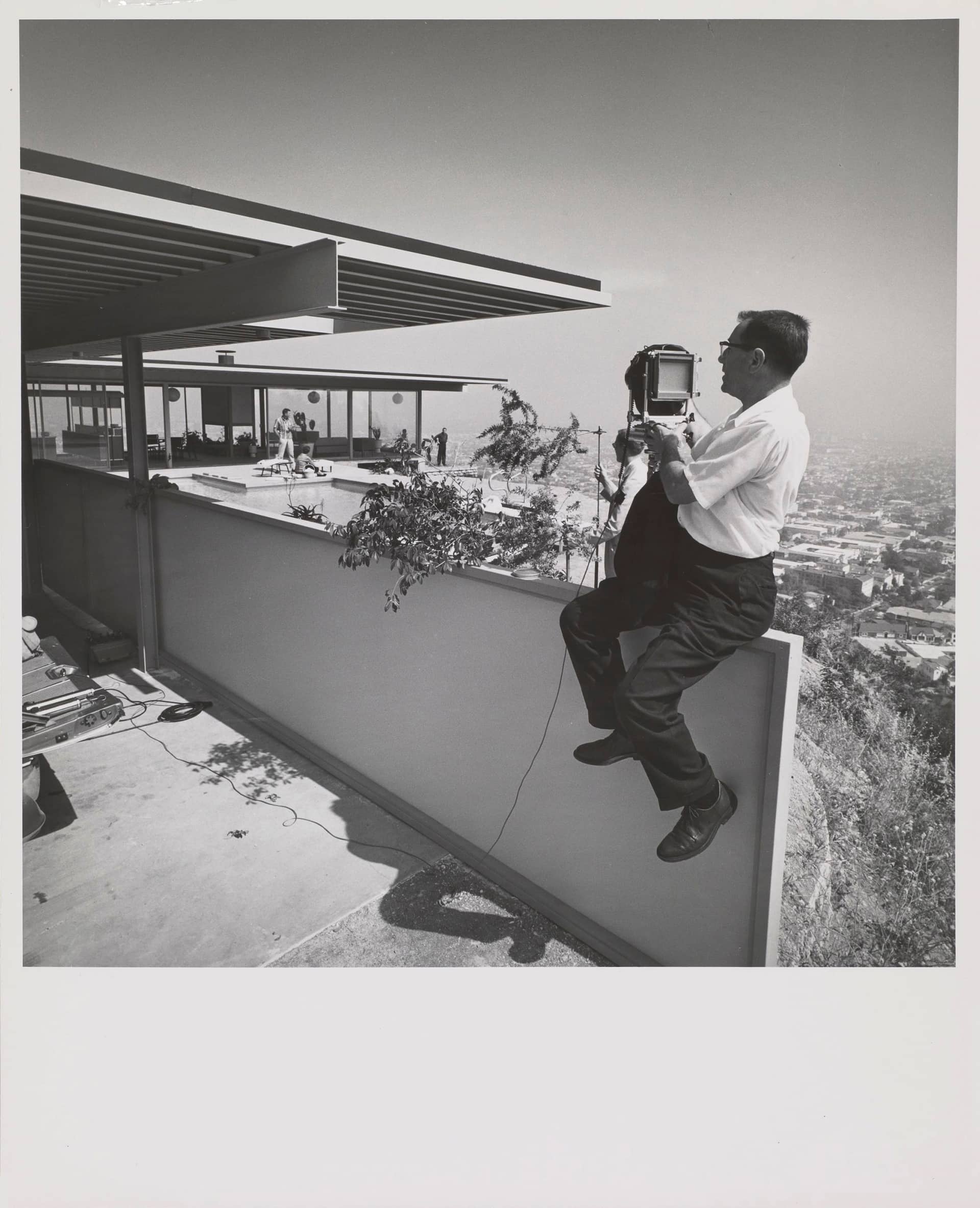

The Case Study architects put modernism into “new clothing” with their use of glass and steel along with post and beam construction, giving residential buildings a more lightweight aesthetic after 1950. If Entenza can be credited with branding this new form of modernism as a lifestyle, it was architectural photographer Julius Shulman who sold it.

Julius Shulman photographing Case Study House #22

For Case Study House #22 (1959–1960), the Stahl House designed by architect Pierre Koenig, Shulman created one of his most widely reproduced images that immortalized the style that came to represent the Case Study House Program and the California Dream. In a brilliant nightscape, Shulman, who photographed 18 of the Case Study Houses, captured the optimistic lifestyle of postwar Los Angeles with two women casually reclining in the glowing living room as it hovers over the sparkling lights of the metropolis below.

While Shulman would say the Stahl House was his most successful photograph, it was actually a composite—the interior and exterior shot separately and the two images superimposed onto one another. Architect, historian and preservationist Alan Hess reveals, “Shulman constructed a lot of his images, but he was selling the story of how modern life in California was so appealing in its spaciousness, openness, use of nature, hillside sites and furnishings. It is in some ways a fantasy, and that lifestyle is what people are still trying to recreate today.”

“The house…will be conceived within the spirit of our time…best suited to the expression of man’s life in the modern world.”

Postwar housing was about mass production, so the ultimate example was Case Study House #8 (1945–1949)—the Charles and Ray Eames house—because it was built with prefabricated industrial parts that were assembled. The same year Charles Eames, along with Eero Saarinen, designed Case Study House #9 for Entenza to occupy the same lot. They worked with Alexander Girard, designer for Herman Miller, to create the furnishings and fabrics for both.

What Entenza succeeded in doing so effectively with the Case Study House Program was capturing and sharing the important ideas that were bubbling up in Southern California during the mid-20th century. His project was forward-thinking—bringing together the best young design talents to solve the problems of the day.

ABOVE: Case Study House #22

Happily, most Case Study Houses are on the National Register of Historic Places, and mid-century modern homes are highly sought-after. However, there was a period when modernism and the Case Study Houses fell out of favor.

As early as the 1960s, there was a movement away from modernism. Frances Anderton, host of DnA: Design and Architecture on KCRW in Los Angeles, explains it this way: “Intellectuals like Robert Venturi and Michael Graves on the East Coast were saying, ‘Bring back some decoration. We want to get away from this stripped-down, getting-everything-down-to-bare-essentials and doctrinaire approach to building.’ All these architects who looked for a breaking out of the box—what now comes under the umbrella of postmodernism—were trained in the modernist ethos at the schools they’d gone to, but they just wanted to do something different and experiment. In Los Angeles, Frank Gehry was a part of that.”

By the end of the 1980s postmodernism was waning, and interest in modernism was on the upswing. Anderton believes that postmodernism was ultimately an architectural style that lived largely on paper and didn’t provide the same fully rounded building system and lifestyle as modernism.

Case Study House #9

While there may have been other contributing factors, the revival of interest in the Case Study House Program was greatly influenced by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles exhibition Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses, curated by Elizabeth A. T. Smith, 1989–1990. The exhibition catalogue provides detailed information on each of the Case Study Houses, as well as illuminating thoughts by important architectural historians, including Esther McCoy’s final essay on the subject.

Perhaps most interesting was The Museum of Contemporary Art’s decision to extend and update the Case Study House Program by inviting six architects and designers—Itsuko Hasegawa, Craig Hodgetts, Toyo Ito, Robert Mangurian, Eric Owen Moss and Adèle Naudé Santos—to contribute their own designs for experimental housing reflecting the spirit of their times.

2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the Case Study House Program. This presents an opportunity to once again consider the program’s legacy and how it continues to impact architectural design in 21st-century Los Angeles, as well as explore the possibility of a future Case Study House Program. For that, I turned to two Los Angeles firms whose practices are rooted in the tenets of modernism.

Steven Ehrlich and Takashi Yanai, principals at Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects, point to the innovative spirit of the city that set the stage for the Case Study House Program as its lasting legacy—beginning with the Schindler House that Ehrlich calls, “the big bang of modern architecture.” Yanai says, “The Case Study House Program is a moment that crystallized that spirit of a young, modern architect coming to Los Angeles. Having the ability to experiment and having that be accepted was a very important aspect of the program. That spirit of experimentation has continued these 75 years.”

Case Study House #9

Which begs the question: Would it be possible to have a Case Study House Program today? If so, how would it be the same, and how would it be different?

David Thompson, second-generation architect and founding principal at Assembledge+, believes it would require another visionary champion like Entenza, who understood that architects were uniquely qualified—by virtue of their education and training—to tackle the social issues of the time and allowed them to express their creative vision unencumbered.

David’s father and principal of Urban Design, Richard Thompson, agrees that while Entenza took a progressive approach, there was an important omission in the program that would need to be considered today. “From a planning perspective, it didn’t deal with neighborhoods, parks, community centers, schools or any of the things we now know and need to address if we are going to have a similar design effort focused on how to build housing. It’s not just about isolated houses but communities … and transportation would be a part of that.”

“Quality of life should not be a luxury commodity for the few.”

Both firms uphold their commitment to environmental stewardship as one of the paramount concerns today, with a renewed interest in smaller, more efficient structures that sit lighter on the land. Technology’s new role would be to sustain the house as a relationship between the people and the environment by integrating the design more holistically on the property.

This would be a change from Entenza’s mandate to incorporate aspects of the home that were energy-intensive, because it was believed at the time that technology could improve your life. Today we still want technology to improve our lives, but not at the expense of the planet.

Case Study House #9

With the lack of affordable housing, homelessness and density issues plaguing Los Angeles, it is questionable whether Entenza’s Case Study House Program model of a single-family house—for a nuclear family on a single plot of land—is sustainable. Most agree that a Case Study Housing Program would be more appropriate for the new millennium, but just as valuable to address the social issues of our time. These issues include the shift away from the suburbs back to the city by millennials who don’t share the American dream of home ownership and prefer to live close to work and mass transit; the changing definition of “family,” the movement away from extended family living by young people, and the desire for communal living by singles and seniors; and perhaps most pressing: the growing sense of isolation and loneliness in today’s society where people crave community.

While architects cannot solve all these problems, which are so much a part of the culture and the economy, the effort Entenza made 75 years ago with Arts & Architecture magazine was a worthy one. So I throw down the gauntlet in hopes that a new visionary will take up the charge, because quality of life should not be a luxury commodity for the few. Though times have changed, one thing is constant: Good design can inspire, uplift and shape all our lives for the better.

An Oakland Park Basketball Court Was in Disrepair Until a Local Star Made a Generous Move

One tweet made all the difference.

Hey, Weekend: Say Cheese

Cheese lovers rejoice! Taste your way up the California coast with these artisan makers.

This Santa Cruz Company Is the First Cannabis Farm Cleared for a Public Stock Offering by the SEC

Will Goldenseed soar on the stock exchange?

Get the Latest Stories